雅思阅读精读:提升阅读成绩的不二法门

雅思阅读精读是提升阅读成绩的不二法门。小编给大家带来了雅思阅读精读,希望能够帮助到大家,下面小编就和大家分享,来欣赏一下吧。

雅思阅读精读:提升阅读成绩的不二法门

认真选择精读文章,只需10篇剑桥文章,你的成绩就可以在7.5以上。(前提是你不是流于形式,而是走心的)闲的蛋疼的学霸可以精读个30篇,8.5以上妥妥的。

我一直认为精读最大的目的在于四点:

生词+学科核心生词;每道题涉及解题的同义替换;长难句的不回读训练;段落中心句位置+文章构架的积累训练与开悟体验

雅思阅读精读1.生词+学科核心生词

学生公认精读来扫清阅读单词死角是再合适不过的了,尤其精读了几篇生物类文章,再答生物类全都认识了。

比如C7蚂蚁智能里面的forage/scout/bearing/odour等词,精读过少量生物类文章,再去做OG上的swarm之类的文章就非常easy了,通篇可以快速读懂,准确定位,正确率超高。

再如精读过C9的金星凌日,天文类词汇基底你就get到了,什么日食月食轨道运行太阳黑子与光斑,只要考试出了天文类,百分之75以上的基底词汇你都是认识的,答题就自如多了。

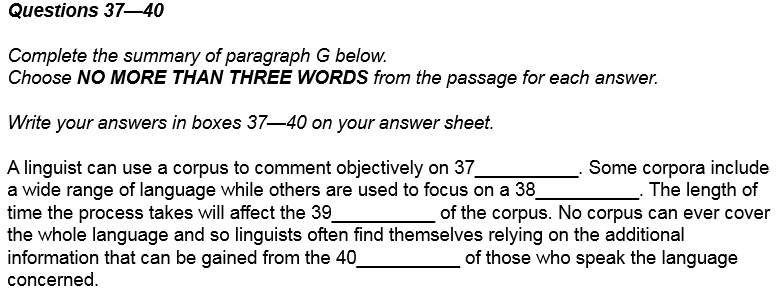

雅思阅读精读2.每道题涉及解题的同义替换

刚好写了个回答关于:雅思阅读每次大概定位准确了,但是精准的定位总是偏差一点,怎么破?!?

粗定位一个定位词,全文没准儿30多处,俗话说:两点定一线,你的关键词/定位词,至少要画两个以上还要全都找到。我一般建议学生“抓三点”“抓四点”“抓五点”,题配句,词换词,细定位就是要找至少两三个换的词。

说到底,同义替换词这个事情,还是要多多积累的,比积累词汇量在雅思阅读中,还要重要。

所以单词量达到瓶颈以后,要做的是背“同义替换词表”

雅思阅读精读3.长难句的不回读训练

忘了是哪个老师跟我说过:三行以上必出题。

N个学生的反馈都是:长难句读到后半句,前面就忘了度过了什么。OR 单词都认识,就是读文章速度太慢。

当年考GMAT看过一本《GMAT长难句练习》,里面提到了”打死我也不回读”这个方法,一直分享给学生,效果反馈很棒。里面说:

只要每天练习五个长难句不回读训练,看到大长句子,习惯性切割主谓宾,一周就会看到效果。本来想着不就是主谓宾嘛,结果练了十多天,读题速度有了飞跃性的提升。

长难句再也不是问题,看到就自动读主谓宾,这就可以轻松记住意思,读下面句子的时候,逻辑就形成了非常舒服的衔接。如果有题在句子中,再去精读也不迟。

雅思阅读精读4.段落中心句位置+文章构架的积累训练与开悟体验

LOH(List of Headings)和 段落信息配对,怎么做,主要靠精读的这个步骤。

LOH做多了,自然有了feel,首句中心句?末句中心句?转折中心句?这就不细说了,做多了就知道。

段落信息配对题,俗称断子绝孙题,因为无序且恶心,同义替换幅度较大,有时候需要通读全文。我却始终坚信“预测乃解决断子绝孙题的直通车”。只要精读了,你就会发现,原来文章各个部位都有暗示你过,那么下次如果你没读原文直接做MATCHING你要怎么“蒙题”,精读多了你就懂了……

BTW,精读之前,务必掐着时间做题,剑桥文章有限珍贵,不能上来直接精读,不要浪费掐时间的机会!

雅思阅读素材积累:Now you know

雅思阅读:Now you know

When should you teach children, and when should you let them explore?

IT IS one of the oldest debates in education. Should teachers tell pupils

the way things are or encourage them to find out for themselves? Telling

children "truths" about the world helps them learn those facts more quickly. Yet

the efficient learning of specific facts may lead to the assumption that when

the adult has finished teaching, there is nothing further to learn—because if

there were, the adult would have said so. A study just published in Cognition by

Elizabeth Bonawitz of the University of California, Berkeley, and Patrick Shafto

of the University of Louisville, in Kentucky, suggests that is true.

Dr Bonawitz and Dr Shafto arranged for 85 four- and five-year-olds to be

presented, during a visit to a museum, with a novel toy that looked like a

tangle of coloured pipes and was capable of doing many different things. They

wanted to know whether the way the children played with the toy depended on how

they were instructed by the adult who gave it to them.

One group of children had a strictly pedagogical introduction. The

experimenter said "Look at my toy! This is my toy. I'm going to show you how my

toy works." She then pulled a yellow tube out of a purple tube, creating a

squeaking sound. Following this, she said, "Wow, see that? This is how my toy

works!" and then demonstrated the effect again.

With a second group of children, the experimenter acted differently. She

interrupted herself after demonstrating the squeak by saying she had to go and

write something down, thus suggesting that she might not have finished the

demonstration. With a third group, she activated the squeak as if by accident.

To a fourth, the toy was simply presented with the comment, "Wow, see this toy?

Look at this!"

After these varied introductions, the children were left with the toy and

allowed to play. They might discover that, as well as the squeaker, the toy had

a button inside one tube which activated a light, a keypad that played musical

notes, and an inverting mirror inside one of the tubes. All the children were

told to let the experimenter know when they had finished playing and were asked

by the instructor if they were done if they stopped playing for more than five

consecutive seconds. The entire interaction was recorded on video.

Footage of each child playing was passed to a research assistant who was

ignorant of the purpose of the study. The assistant was asked to record the

total playing time, the number of different actions the child performed, the

time spent playing with the squeak, and the number of other functions the child

discovered.

The upshot was that children in the first group spent less time playing

(119 seconds) than those in the second (180 seconds), the third (133 seconds) or

the fourth (206 seconds). Those in the first group also tried out four different

actions, on average. The others tried 5.3, 5.9 and 6.2, respectively. A similar

pattern (0.7, 1.3, 1.2 and 1.2) pertained to the number of functions other than

the squeak that the children found.

The researchers' conclusion was that, in the context of strange toys of

unknown function, prior explanation does, indeed, inhibit exploration and

discovery. Generalising from that would be ambitious. But it suggests that

further research might be quite a good idea

雅思阅读素材积累:Whose lost decade?

Japan's economy works better than pessimists think—at least for the

elderly.

THE Japanese say they suffer from an economic disease called "structural

pessimism". Overseas too, there is a tendency to see Japan as a harbinger of all

that is doomed in the economies of the euro zone and America—even though figures

released on November 14th show its economy grew by an annualised 6% in the third

quarter, rebounding quickly from the March tsunami and nuclear disaster.

Look dispassionately at Japan's economic performance over the past ten

years, though, and "the second lost decade", if not the first, is a misnomer.

Much of what tarnishes Japan's image is the result of demography—more than half

its population is over 45—as well as its poor policy in dealing with it. Even

so, most Japanese have grown richer over the decade.

In aggregate, Japan's economy grew at half the pace of America's between

2001 and 2010. Yet if judged by growth in GDP per person over the same period,

then Japan has outperformed America and the euro zone (see chart 1). In part

this is because its population has shrunk whereas America's population has

increased.

Though growth in labour productivity fell slightly short of America's from

2000 to 2008, total factor productivity, a measure of how a country uses capital

and labour, grew faster, according to the Tokyo-based Asian Productivity

Organisation. Japan's unemployment rate is higher than in 2000, yet it remains

about half the level of America and Europe (see chart 2).

Besides supposed stagnation, the two other curses of the Japanese economy

are debt and deflation. Yet these also partly reflect demography and can be

overstated. People often think of Japan as an indebted country. In fact, it is

the world's biggest creditor nation, boasting ¥253 trillion ($3.3 trillion) in

net foreign assets.

To be sure, its government is a large debtor; its net debt as a share of

GDP is one of the highest in the OECD. However, the public debt has been accrued

not primarily through wasteful spending or "bridges to nowhere", but because of

ageing, says the IMF. Social-security expenditure doubled as a share of GDP

between 1990 and 2010 to pay rising pensions and health-care costs. Over the

same period tax revenues have shrunk.

Falling tax revenues are a problem. The flip side, though, is that Japan

has the lowest tax take of any country in the OECD, at just 17% of GDP. That

gives it plenty of room to manoeuvre. Takatoshi Ito, an economist at the

University of Tokyo, says increasing the consumption tax by 20 percentage points

from its current 5%—putting it at the level of a high-tax European country—would

raise ¥50 trillion and immediately wipe out Japan's fiscal deficit.

That sounds draconian. But here again, demography plays a role. Officials

say the elderly resist higher taxes or benefit cuts, and the young, who are in a

minority, do not have the political power to push for what is in their long-term

interest. David Weinstein, professor of Japanese economy at Columbia University

in New York, says the elderly would rather give money to their children than pay

it in taxes. Ultimately that may mean that benefits may shrink in the future.

"If you want benefits to grow in line with income, as they are now, you need a

massive increase in taxes of about 10% of GDP," he says.

Demography helps explain Japan's stubborn deflation, too, he says. After

all, falling prices give savers—most of whom are elderly—positive real yields

even when nominal interest rates are close to zero. Up until now, holding

government bonds has been a good bet. Domestic savers remain willing to roll

them over, which enables the government to fund its deficits. Yet this comes at

a cost to the rest of the economy.

In short, Japan's economy works better for those middle-aged and older than

it does for the young. But it is not yet in crisis, and economists say there is

plenty it could do to raise its potential growth rate, as well as to lower its

debt burden.

Last weekend Yoshihiko Noda, the prime minister, took a brave shot at

promoting reform when he said Japan planned to start consultations towards

joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership. This is an American-backed free-trade

zone that could lead to a lowering of tariffs on a huge swath of goods and

services. Predictably it is elderly farmers, doctors and small businessmen who

are most against it.

Reforms to other areas, such as the tax and benefit system, might be easier

if the government could tell the Japanese a different story: not that their

economy is mired in stagnation, but that its performance reflects the ups and

downs of an ageing society, and that the old as well as the young need to make

sacrifices.

The trouble is that the downbeat narrative is deeply ingrained. The current

crop of leading Japanese politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen are themselves

well past middle age. Many think they have sacrificed enough since the glory

days of the 1980s, when Japan's economy seemed unstoppable. Mr Weinstein says

they suffer from "diminished-giant syndrome", nervously watching the economic

rise of China. If they compared themselves instead with America and Europe, they

might feel heartened enough to make some of the tough choices needed.

雅思阅读精读:提升阅读成绩的不二法门相关文章:

★ 雅思阅读怎样才算精读