最优雅思阅读解题思路分析, 适合自己的大约是最好的,小编给大家带来了最优雅思阅读解题思路分析,希望能够帮助到大家,下面小编就和大家分享,来欣赏一下吧。

最优雅思阅读解题思路分析 适合自己的大约是最好的

雅思阅读疑难问题1. 先看文章还是先看题目?

这里提到的看文章,指的是通读全文。做题前,到底需不需要先看完整篇文章呢?

同学纠结的是,不看完整篇文章理解不透,怎么做题?可是看完了整篇文章,未必有充足的时间做题,怎么办?

其实这个问题但凡新烤鸭都要涉及,只是不会一开口就给定论,因为每个人都不一样,所谓的好方法不一定适合每一个人。开课时,我会稍微介绍一下雅思阅读考试,然后给学员一篇文章练手,请他们用自己的,无论什么方法,在20分种内尽量去完成这些题目,同时观察他们的表现——速度、正确率。我觉得这些能很好地帮助我了解他们——尤其是新成员——的基本情况,比如词汇量、文法等等,然后再根据他们的完成情况来给出不同的意见。

如果学员用自己的方法完成得很好,无论他们先看文章还是先看题目,我觉得都不重要。我会请他们坚持自己的做法,不必介意孰先孰后。因为别人的方法不管多好也都是别人的,只有自己的方法才能用得最顺手。比如,寒假班就有一个女生,她就是先看完整篇文章才做题的,速度很快,而且最终阅读单科取得了满分。而暑假班有一个男生,他就是先看题目再去做题的,速度也很快,最终阅读也考了满分。倘若自己有方法,又能保证效率和精确率,何必介怀我的做法与别人的不同呢?

不过,如果你没有那么厉害的词汇量、不凡的理解力,而且根据自己的方法做得不如意,或者自己根本就没有概念应该怎么做,then we are ready to help you. 做阅读题时,大部分的学员在有限的时间内,如果先看完文章再做题目通常无法高效、准确地达到目的,而且大多数题目并不需要通读全文。鉴于此,建议大部分同学直接看题目,再根据题目中的定位词有针对性地去文中搜索答案,以达到省时、精确的目的。

雅思阅读疑难问题问题2. 做题前是否要看每个段落的首末句?

既然不需要通读全文,那么有些老师就会建议同学在做题之前,先预览一下每个段落的首末句,以达到了解全文大意的目的。

能迅速、精确地理解每段首末句固然可贵,但不一定所有同学都能办到。

事实是,很多同学看句子很慢,而且理解得不那么轻松,就算坚持把每段的首末句都看完,也不一定能理解到位。尤其是雅思阅读考试,不是所有的文章都有考到List of Headings等主旨题的,不少文章都是考细节的题目,就算看了首末句也未必能帮助我们解题。而对于各位考生而言,解题才是首要任务。再则,理解全文大意真的需要这么大费周章吗?理解了全文标题不也可以办到?请看例子:

Cambridge 5 Test 2 Passage 3 ‘The Birth of Scientific English’

Cambridge 5 Test 3 Passage 3 ‘The Return of Artificial Intelligence’

看了这两篇文章的题目能马上明白全文大意和主要方向吧?

这个太简单?换一个!找篇题目是生词的文章:

Cambridge 8 Test 1 Passage 3 ‘Telepathy’

很多人不认识这个词,怎么办?看导语或者首段,通常会对标题进行解释。所以一看标题下方的导语‘Can human beings communicate by thought alone?’有没有马上清楚文章的走向?

所以,对于理解句子不是特别专长的同学,做题的时候可以略去这个步骤,改为理解文章的框架,也就是标题,插图或是首段等等。

雅思阅读疑难问题3. 先做填空类的还是选择类的题目?

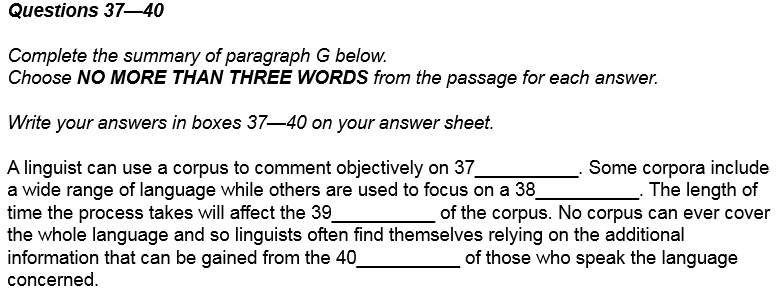

雅思阅读的题型总体可以归为两种:填空类和选择类。

填空类,比如摘要题summary, 句子填空题sentence completion, 简答题short-answer questions以及图表题diagrams;

选择类,比如段落大意题list of headings, 选择题multiple choice, 是非无判断题TRUE/FALSE/NOT GIVEN, 还有各种匹配题matching。

在熟悉了各种题型后,有些同学也许会发现自己的薄弱题型,有些同学可能还没有明确的概念。一些老师建议同学考试的时候先做填空类的题目,我认为这个建议可圈可点,考虑到有些同学在单位时间内根本做不完题目,那么如果先做填空题会相对减少一点风险,毕竟到最后一分钟,如果剩下的是选择类题型,还有机会蒙,如果剩下的是填空题,岂不是连蒙的机会都基本没有了?所以,个人认为,对于填空题还比较擅长但速度上不去的同学而言,这是个不错的建议。

不过,那些做填空类题目并不太擅长的同学要慎用上面的建议,因为时间要花在刀刃上。试想一下,如果我们在时间比较充足的情况下,却把大部分时间浪费在我们做不对的题目上,而导致选择类题目有可能做对,却全交给命运来蒙,是不是太遗憾了呢?

在单位时间内保证正确率是最重要的,所以,我建议同学们先做自己擅长的题型,不管哪一种。

雅思阅读疑难问题4. 是否要按照文章或者题目的排列顺序做题呢?

大家都知道,雅思阅读大部分的套题中,文章的难度系数都是递增的,所以是不是做题的时候按顺序从第一篇做到第三篇比较好呢?或者说一开始把第三篇先做了,迎难而上?

不知道各位有没有注意到,几乎每次看考生在考试后写的考试回顾,总会看到有同学说这次阅读题好难,也会有同学回忆这次阅读题好简单。这很正常,因为每个人对于难度的理解是不一样的,从专业的角度来看也许挺难的,可有一些同学就是刚好就对了。就好像看歌唱比赛,有时观众觉得唱得特别好的却被专家否决,观众觉得不怎么样的却挺进前几名甚至拿下冠军。有时候并不是比赛不公正,只是因为我们还不够专业,不能抓住要领罢了。所以就算第三篇阅读比较难,也会有一些同学觉得so so, 而且三篇未做完之前,大家根本就不能保证一定是第三篇最难还是最简单。有时候我们觉得第三篇特别难或许只是因为考试时间快结束了,心里特别紧张使得题目的难度无形中加大,所以不如调整好心态,给每篇文章尽量充足的时间。

所以我经常在上课的时候说,如果考试的时候,大家速度还没那么快,那可以接受自己每篇都有几道题做不出来,但是不能接受前面全做了,到最后一篇几道题还来不及看时间已经到了。听起来好像效果是一样的,但是过程却有很大不同。每篇都有几道题没做出来,是因为我们看了,可是不会(要么单词不懂,要么定位不到,要么句子不能理解透),不管什么原因,碰到这种情况建议果断跳过蒙个答案,就算错了也不可惜;可是剩余题目没来得及看就被宣判死刑,我们怎么知道我们一定做不出来呢?

至于题目顺序,我倒是觉得先做哪道题是无所谓的,我们的目标只有一个:在有效的时间内尽快做对我们能应付得来的题目。所以,如果第三题能先找到,为什么一定要拘泥于题目的序号,从第一题开始做呢?

来给大家举个例子:

Cambridge 4 Test 3 Passage 3 ‘The Return of Artificial Intelligence’

Questions 32-37

32. The researchers who launched the field of AI had worked together on other projects in the past.

33. In 1985, AI was at its lowest point.

34. Research into agent technology was more costly than research into neural networks.

35. Applications of AI have already had a degree of success.

36. The problems waiting to be solved by AI have not changed since 1967.

37. The film 2001: A Space Odyssey reflected contemporary ideas about the potential of AI computers.

比如上面这几道题,我们知道判断题大多为顺序题型,而33、36题中分别有数字1985和since 1967; 37题中有斜体2001: A Space Odyssey, 如果利用这些特征,先做这三题是不是能更快速找到答案?然后在33和36中间找34、35题,在33题前面找32题,会不会更容易呢?为什么一定要从头开始做呢?

雅思阅读素材积累:A Drier and Hotter Future

While I was reading William deBuys's new book, A Great Aridness, two massive dust storms reminiscent of the 1930s raged across the skies of Phoenix and of Lubbock, Texas. Newspapers blamed them on the current drought in the West, which is proximately true. But what ultimately is causing this drought, and why would any drought produce such terrifying clouds of dust? The answer is that they may be portents of a more threatening world that we humans are unwittingly creating. As deBuys explains, "Because arid lands tend to be underdressed in terms of vegetation, they are naturally dusty. Humans make them dustier."

Agriculture is the main reason for those dust storms—the clearing of native grasslands or sagebrush to grow cotton or wheat, which die quickly when drought occurs and leave the soil unprotected. Phoenix and Lubbock are both caught in severe drought, and it is going to get much worse. We may see many such storms in the decades ahead, along with species extinctions, radical disturbance of ecosystems, and intensified social conflict over land and water. Welcome to the Anthropocene, the epoch when humans have become a major geological and climatic force.

DeBuys is an acclaimed historian turned conservationist in his adopted home of the Southwest. A Great Aridness is his most disturbing book, a jeremiad that ought to be required reading for politicians, economists, real-estate developers and anyone thinking about migrating to the Sunbelt. In the early chapters he reports on the science of how and why precipitation and ecology are changing, not predictably but in nonlinear ways that make the future very uncertain and dark. In later chapters he visits ancient pueblo ruins left behind by earlier civilizations that were destroyed by drought, and he follows the grim trail of migrants crossing the border from Mexico, stirring up a controversy that climate change can only exacerbate. The book is an eclectic mix of personal experience, scientific analysis and environmental history.

Smoke as well as dust is spoiling the southwestern skies. As deBuys points out, forest fires are getting much bigger. In June 2002 the Rodeo and Chediski fires erupted on Arizona's Mogollon Plateau, soon merging into a single conflagration that consumed nearly 500,000 acres. It was Arizona's largest fire—until the Wallow Fire eclipsed it in June 2011. Another devastating effect of climate change has been the explosion of bark beetles among western pines, which in turn contributes to the new fire regime; in 2003, dead trees covered 2.6 million acres in Arizona and New Mexico. Could anything be more demoralizing than the sight of green forests turned a grisly brown, then bursting into flame and left charred and black?

Even more depressing than declining forests are mountains bare of snow. When future springs arrive, the sound of running water will be much diminished. The biggest environmental catastrophe for the Southwest, already our most arid region, is losing the melting runoff from snowpacks into rivers, canals and irrigation ditches. An ominous chapter in the book examines the future of the Colorado River, which for decades has been the "blood" of the Southwest's oasis civilization. In the 1920s Americans divided the river between upper and lower basins, allocating to each a share of the annual flow. California, which contributes almost nothing to the river, sucks up the largest share of any state, spreading it across the Imperial Valley's agricultural fields and diverting the rest to Los Angeles. Years ago policy makers assumed that the river carried about 17 million acre-feet of water per year—that is, enough water to cover 17 million acres to a depth of one foot. They overestimated, as people tend to do when hope and greed outrun the facts. Now comes a drier and hotter future, when the Colorado River will carry even less water—perhaps as little as 11 million acre-feet.

Tim Barnett and David Pierce of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography estimate that to adjust to a sustainable level of supply, consumers of Colorado River water will have to get along with 20 percent less water than they use today. That is still a lot of water to lose, but the loss may not be catastrophic. Urban users are already conserving about as much as they can per capita. Farmers, on the other hand, who consume about 80 percent of the western water supply, including in California, are wasting much through inefficient management and low-value crops. Half of the water goes to raise alfalfa to feed cattle, and much of the rest evaporates or soaks into the sand. If some of agriculture's share could be diverted to cities, there might be enough to sustain the current population. Rural communities would decline, some lucky farmers would retire with a potful of money, and the public would have to figure out where to get its lettuce, tomatoes, oranges and meat. The cost of water would go up dramatically, and those without money would go thirsty and leave. New hierarchies would take the place of old ones.

Thirty million people now depend on the Colorado River. Perhaps they can manage to adjust to a diminished flow and to declines in domestic food supplies and hydroelectric power. But more people are on the way: Demographers calculate that the population of the Southwest may increase by 10 or 20 million between now and 2050. Some of those people will come from other parts of the country, some from Mexico and Central America, and some from other nations that are coping poorly with their current problems or are overwhelmed by climate change. Whatever their origin, the new arrivals will go to the familiar oases, hoping to find the good life with a swimming pool and a green lawn.

Developers are eager to make money by selling homes to these newcomers. The political and economic culture of the Southwest is dead set against any acknowledgment of limits to growth. In the last few chapters of the book, deBuys shows that even now those in power refuse to accept any check to expansion; business must be free to do business. Others say that they are helpless to stop the influx: Patricia Mulroy, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority in Las Vegas, declares, "You can't take a community as thriving as this one and put a stop sign out there. The train will run right over you." Her solution is to create an expensive "straw" to extract water from a shrinking Lake Mead, drawing on the "dead pool" that will be left below the intakes for generating electricity. She doesn't have the money to build that straw right now, but she is working hard to keep her improbable city from drying up and becoming a casualty like ancient Mesopotamia. Similarly, Phoenix continues to issue building permits helter-skelter and counts on "augmenting the supply" of water sometime in the future. But where will the state and city go for more supply, and how will they bring it cheaply over mountains and plains to keep Phoenix sprawling into the sunset?

DeBuys gathers enough scientific evidence to make a convincing case against that growth mentality. A similar case could be made against growth in the rest of the United States, although in the East the threat may be too much water, not too little, and too many storms, not too much smoke and dust. The past warns us that ancient peoples once failed to adapt and survive. Will theirs be America's fate? Perhaps. But past human behavior may not be a reliable indicator of how people will behave in the future. If the environment is becoming nonlinear and unpredictable, as deBuys argues, then human cultures may also become nonlinear and unpredictable. No other people have had as much scientific knowledge to illuminate their condition. What we will do with that knowledge is the biggest imponderable of all.

最优雅思阅读解题思路分析相关文章:

★ 3个月备考期的雅思阅读复习经验

★ 雅思阅读简答题解题技巧

★ 雅思阅读解题技巧

★ 雅思阅读各类题型和解题技巧汇总

★ GRE等价题解题思路实例分析

★ GRE填空等价题高分解题思路实例分析

最优雅思阅读解题思路分析

适合自己的大约是最好的,小编给大家带来了最优雅思阅读解题思路分析,希望能够帮助到大家,下面小编就和大家分享,来欣赏一下吧。最优雅思阅读解题思路分析 适合自己的大约是最好的雅思阅读疑难问题1. 先看文章还是先看题。下面小编给大家分享最优雅思阅读解题思路分析,希望能帮助到大家。 最优雅思阅读解题思路分析文档下载网址链接:

下一篇:返回列表