如何上手雅思阅读,并最终熟练即使地完成所有的40道题目呢?下面小编给大家带来了雅思阅读考试的3大必杀技讲解,希望能够帮助到大家,下面小编就和大家分享,来欣赏一下吧。

雅思阅读考试的3大必杀技讲解

首先,拥有扎实的词汇语法基础及丰富的背景知识。

这里强调的其实是英文基础的重要性。考生想要在考试过程中游刃有余,没有一定的词汇量基本是没有办法达成的。当然我们在考试中可以通过上下文,转折词等等猜测生词的意思。但是,一旦生词量超过一定比例,势必会影响考生的理解。说到理解,在雅思考试中碰到长难句是常有的事情。那么扎实的语法基础也是考生正确理解文章意义的一个重要的必备素质。除去扎实的词汇语法基础之外,丰富的背景知识也是一名高分考生所必须的。

雅思阅读考试人文社科类和自然科学类当中有众多小分支话题,涉及天文、地理、生物、地质、语言学、发展史等等众多领域。为了保证考试时的阅读效率及答题的正确性,考生需要在平时多多查阅相关资料,了解各类文章背景。至于常考的老话题及最新出现的新话题,考生可以通过对于机经的总结去获取相关信息。另外,在了解各类相关背景文章的同时,考生还可以增加相关的词汇量,实是一举两得的好办法。

其次,了解雅思阅读文章的行文结构。

一般的考生在备考过程中,很少注意培养对于一篇文章的整体把控能力。往往他们会陷于疲于读题,疲于找答案的混乱状态。其实,如果考生对于雅思考试阅读文章的行文结构有一定程度的了解,会大大提高考生答题的效率及准确率,并且节约答题时间。用我们经常会遇到的试验研究类文章举个例子。这种类型的文章开始会介绍这个实验的一些基本情况,如试验主体、试验对象等等,之后往往会介绍试验的具体操作过程,然后是实验的结果,及最终的数据结论。

这样的文章出现,往往会伴随着人物观点题。而自然科学类文章则多为平行结构,对一种现象或生物的各个方面做说明介绍。此类文章结构工整,较易定位。所以,如果考生对于雅思阅读考试的文章结构有所了解的话,即使遇见自己所不熟悉的自然科学类文章,也可根据大致文章结构,快速在原文中定位题目答案所在段落,并且只针对与题目有关的部分进行精读。

第三,洞悉雅思考试的出题角度。

雅思阅读考试的题型多变,有细节题,有大意题,有考察整体理解的题型,也有考察辨别信息能力的题型。因此,建议想要取得高分的学员,在掌握每种题型的解题技巧的同时,还需要研究的是考试的出题角度,仔细研究各种题型考察的是何种能力。然后有针对性的去锻炼这方面的能力。

雅思阅读机经真题回忆及答案解析

一、 考试概述:

本次考试的文章两篇旧题一篇新题,第一篇是关于托马斯杨这个人的人物传记,第二篇是跟仿生科学相关的,讲人们可以利用自然中的现象改善生活,第三篇介绍了四种不同的性格和它们对团队合作的影响。本次考试第一篇及第三篇文章较容易,最难的为第二篇文章,但是很多考生花费很多时间在第二篇上,导致没时间做简单的第三篇文章,所以希望大家考试中能灵活选择做题顺序。

二、具体题目分析

Passage 1:

题目:Thomas Young

题型:判断题7 +简答题6

新旧程度:旧题

文章大意:关于托马斯杨的个人传记

参考文章:

Thomas Young

The Last True Know-It-All

A Thomas Young (1773-1829) contributed 63 articles to the Encyclopedia Britannica, including 46 biographical entries (mostly on scientists and classicists) and substantial essays on "Bridge,” "Chromatics," "Egypt," "Languages" and "Tides". Was someone who could write authoritatively about so many subjects a polymath, a genius or a dilettante? In an ambitious new biography, Andrew Robinson argues that Young is a good contender for the epitaph "the last man who knew everything." Young has competition, however: The phrase, which Robinson takes for his title, also serves as the subtitle of two other recent biographies: Leonard Warren's 1998 life of paleontologist Joseph Leidy (1823-1891) and Paula Findlen's 2004 book on Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680), another polymath.

B Young, of course, did more than write encyclopedia entries. He presented his first paper to the Royal Society of London at the age of 20 and was elected a Fellow a week after his 21st birthday. In the paper, Young explained the process of accommodation in the human eye on how the eye focuses properly on objects at varying distances. Young hypothesized that this was achieved by changes in the shape of the lens. Young also theorized that light traveled in waves and he believed that, to account for the ability to see in color, there must be three receptors in the eye corresponding to the three "principal colors" to which the retina could respond: red, green, violet. All these hypothesis were subsequently proved to be correct.

C Later in his life, when he was in his forties, Young was instrumental in cracking the code that unlocked the unknown script on the Rosetta Stone, a tablet that was "found" in Egypt by the Napoleonic army in 1799. The stone contains text in three alphabets: Greek, something unrecognizable and Egyptian hieroglyphs. The unrecognizable script is now known as demotic and, as Young deduced, is related directly to hieroglyphic. His initial work on this appeared in his Britannica entry on Egypt. In another entry, he coined the term Indo-European to describe the family of languages spoken throughout most of Europe and northern India. These are the landmark achievements of a man who was a child prodigy and who, unlike many remarkable children, did not disappear into oblivion as an adult.

D Born in 1773 in Somerset in England, Young lived from an early age with his maternal grandfather, eventually leaving to attend boarding school. He had devoured books from the age of two, and through his own initiative he excelled at Latin, Greek, mathematics and natural philosophy. After leaving school, he was greatly encouraged by his mother's uncle, Richard Brocklesby, a physician and Fellow of the Royal Society. Following Brocklesby's lead, Young decided to pursue a career in medicine. He studied in London, following the medical circuit, and then moved on to more formal education in Edinburgh, Gottingen and Cambridge. After completing his medical training at the University of Cambridge in 1808, Young set up practice as a physician in London. He soon became a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and a few years later was appointed physician at St. George's Hospital.

E Young's skill as a physician, however, did not equal his skill as a scholar of natural philosophy or linguistics. Earlier, in 1801, he had been appointed to a professorship of natural philosophy at the Royal Institution, where he delivered as many as 60 lectures in a year. These were published in two volumes in 1807. In 1804 Young had become secretary to the Royal Society, a post he would hold until his death. His opinions were sought on civic and national matters, such as the introduction of gas lighting to London and methods of ship construction. From 1819 he was superintendent of the Nautical Almanac and secretary to the Board of Longitude. From 1824 to 1829 he was physician to and inspector of calculations for the Palladian Insurance Company. Between 1816 and 1825 he contributed his many and various entries to the Encyclopedia Britannica, and throughout his career he authored numerous books, essays and papers.

F Young is a perfect subject for a biography - perfect, but daunting. Few men contributed so much to so many technical fields. Robinson's aim is to introduce non-scientists to Young's work and life. He succeeds, providing clear expositions of the technical material (especially that on optics and Egyptian hieroglyphs). Some readers of this book will, like Robinson, find Young's accomplishments impressive; others will see him as some historians have - as a dilettante. Yet despite the rich material presented in this book, readers will not end up knowing Young personally. We catch glimpses of a playful Young, doodling Greek and Latin phrases in his notes on medical lectures and translating the verses that a young lady had written on the walls of a summerhouse into Greek elegiacs. Young was introduced into elite society, attended the theatre and learned to dance and play the flute. In addition, he was an accomplished horseman. However, his personal life looks pale next to his vibrant career and studies.

G Young married Eliza Maxwell in 1804, and according to Robinson, "their marriage was a happy one and she appreciated his work." Almost all we know about her is that she sustained her husband through some rancorous disputes about optics and that she worried about money when his medical career was slow to take off. Very little evidence survives about the complexities of Young's relationships with his mother and father. Robinson does not credit them, or anyone else, with shaping Young's extraordinary mind. Despite the lack of details concerning Young's relationships, however, anyone interested in what it means to be a genius should read this book.

参考答案:

判断题:

1.“The last man who knew everything” has also been claimed to other people. TURE

2. All Young’s articles were published in Encyclopedia Britannica. FALSE

3. Like others, Young wasn't so brilliant when grew up. FALSE

4. Young's talents as a doctor are surpassing his other skills. NOT GIVEN

5. Young's advice was sought by people responsible for local and national issues. TRUE

6. Young was interested in various social pastimes. TRUE

7. Young suffered from a disease in his later years. NOT GIVEN

填空题:

8. How many life stories did Young write for Encyclopedia Britannica? 46

9. What aspect of scientific research did Young do in his first academic paper? human eye

10. What name did Young introduce to refer to a group of languages? Indo-European

11. Who inspired Young to start the medical studies? Richard Brocklesby

12. Where did Young get a teaching position? Royal Institution

13. What contribution did Young make to London? gas lighting

(答案仅供参考)

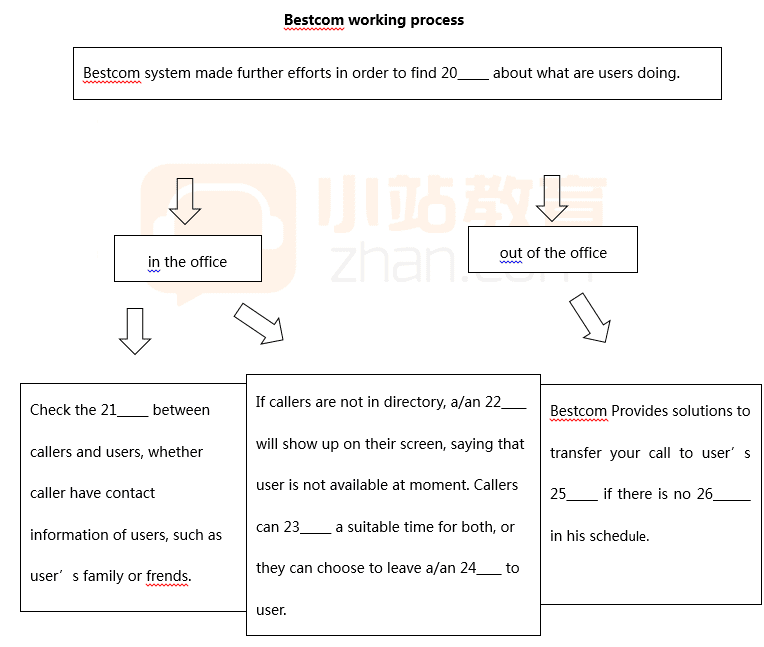

Passage 2:

题目: Learn the nature

题型:段落细节配对4+填空题5+人名理论配对 4

新旧程度:新题

文章大意:讲仿生科学的,写出大自然里有很多现象可以被学习和利用,用于科学研究改善人类社会和生活。

参考文章:

暂无

参考答案:

段落细节配对:

暂无

填空题:

18. sun

19. fog

20. wind

21. mouth

22. roof

人名理论配对题:

暂无

(答案仅供参考)

Passage 3:

题名:Communicating Styles and Conflict

题型:段落主旨大意题8+判断题5+选择题1

新旧程度:旧题

文章大意:四种不同性格的分类和在职场中的表现

参考文章:

Communicating Styles and Conflict

Knowing your communication style and having a mix of styles on your team can provide a positive force for resolving conflict.

Section A

As far back as Hippocrates’ time (460-370 B. C.) people have tried to understand other people by characterizing them according to personality type or temperament. Hippocrates believed there were four different body fluids that influenced four basic types of temperament. His work was further developed 500 years later by Galen (130-200 A. D.). These days there are any number of self-assessment tools that relate to the basic descriptions developed by Galen, although we no longer believe the source to be the types of body fluid that dominate our systems.

Section B

The value in self-assessments that help determine personality style, learning styles, communication styles, conflict-handling styles, or other aspects of individuals is that they help depersonalize conflict in interpersonal relationships. The depersonalization occurs when you realize that others aren’t trying to be difficult, but they need different or more information than you do. They’re not intending to be rude; they are so focused on the task they forget about greeting people. They would like to work faster but not at the risk of damaging the relationships needed to get the job done. They understand there is a job to do, but it can only be done right with the appropriate information, which takes time to collect. When used appropriately, understanding communication styles can help resolve conflict on teams. Very rarely are conflicts true personality issues. Usually they are issues of style, information needs, or focus.

Section C

Hippocrates and later Galen determined there were four basic temperaments: sanguine, phlegmatic, melancholic and choleric. These descriptions were developed centuries ago and are still somewhat apt, although you could update the wording. In today’s world, they translate into the four fairly common communication styles described below:

Section D

The sanguine person would be the expressive or spirited style of communication. These people speak in pictures. They invest a lot of emotion and energy in their communication and often speak quickly, putting their whole body into it. They are easily sidetracked onto a story that may or may not illustrate the point they are trying to make. Because of their enthusiasm they are great team motivators. They are concerned about people and relationships. Their high levels of energy can come on strong at times and their focus is usually on the bigger picture, which means they sometimes miss the details or the proper order of things. These people find conflict or differences of opinion invigorating and love to engage in a spirited discussion. They love change and are constantly looking for new and exciting adventures.

Section E

The phlegmatic person — cool and persevering — translates into the technical or systematic communication style. This style of communication is focused on facts and technical details. Phlegmatic people have an orderly methodical way of approaching tasks, and their focus is very much on the task, not on the people, emotions, or concerns that the task may evoke. The focus is also more on the details necessary to accomplish a task. Sometimes the details overwhelm the big picture and focus needs to be brought back to the context of the task. People with this style think the facts should speak for themselves, and they are not as comfortable with conflict. They need time to adapt to change and need to understand both the logic of it and the steps involved.

Section F

The melancholic person who is softhearted and oriented toward doing things for others translates into the considerate or sympathetic communication style. A person with this communication style is focused on people and relationships. They are good listeners and do things for other people — sometimes to the detriment of getting things done for themselves. They want to solicit everyone’s opinion and make sure everyone is comfortable with whatever is required to get the job done. At times this focus on others can distract from the task at hand. Because they are so concerned with the needs of others and smoothing over issues, they do not like conflict. They believe that change threatens the status quo and tends to make people feel uneasy so people with this communication style, like phlegmatic people, need time to consider the changes in order to adapt to them.

Section G

The choleric temperament translates into the bold or direct style of communication. People with this style are brief in their communication — the fewer words the better. They are big picture thinkers and love to be involved in many things at once. They are focused on tasks and outcomes and often forget that the people involved in carrying out the tasks have needs. They don’t do detail work easily and as a result can often underestimate how much time it takes to achieve the task. Because they are so direct, they often seem forceful and can be very intimidating to others. They usually would welcome someone challenging them, but most other styles are afraid to do so. They also thrive on change, the more the better.

Section H

A well-functioning team should have all of these communication styles for true effectiveness. All teams need to focus on the task, and they need to take care of relationships in order to achieve those tasks. They need the big picture perspective or the context of their work, and they need the details to be identified and taken care of for success. We all have aspects of each style within us. Some of us can easily move from one style to another and adapt our style to the needs of the situation at hand — whether the focus is on tasks or relationships. For others, a dominant style is very evident, and it is more challenging to see the situation from the perspective of another style. The work environment can influence communication styles either by the type of work that is required or by the predominance of one style reflected in that environment. Some people use one style at work and another at home. The good news about communication styles is that we all have the ability to develop flexibility in our styles. The greater the flexibility we have, the more skilled we usually are at handling possible and actual conflicts. Usually it has to be relevant to us to do so, either because we think it is important or because there are incentives in our environment to encourage it. The key is that we have to want to become flexible with our communication style. As Henry Ford said, "Whether you think you can or you can’t, you’re right!"

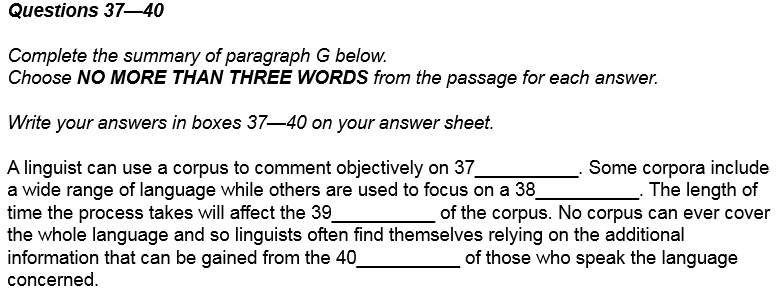

参考答案:

段落主旨大意题:

27. iii

28. vii

29. i

30. iv

31. ix

32. viii

33. v

34. ii

判断题:

35. It is believed that sanguine people dislike variety. FALSE

36. Melancholic and phlegmatic people have similar characteristics. TRUE

37. Managers often select their best employees according to personality types. NOT GIVEN

38. It is possible to change one’s personality type. TRUE

39. Workplace environment can affect which communication style is most effective. TRUE

选择题:

40. The writer believes using self-assessment tools can B. help to understand colleagues’ behavior

(答案仅供参考)

雅思阅读考试的3大必杀技讲解

上一篇:搞定同义词替换就是搞定雅思阅读

下一篇:返回列表